How Much Does A World Cup Cost?

It is one of the world’s biggest sporting events, the FIFA World Cup, and similar to how keen companies are to sponsor the event, many countries dream of hosting it. However, revenue often does not compensate for costs that run into the billions. It is a long process from starting the bid process until the tournament takes place. And even after the tournament ends, costs are incurred.

It is one of the world’s biggest sporting events, the FIFA World Cup, and similar to how keen companies are to sponsor the event, many countries dream of hosting it. However, revenue often does not compensate for costs that run into the billions. It is a long process from starting the bid process until the tournament takes place. And even after the tournament ends, costs are incurred.

So how much does it cost to organise the FIFA World Cup? Is it worthwhile for countries to host football’s biggest event? And what effect will the expansion to 48 teams have?

FIFA’s investment in the World Cup

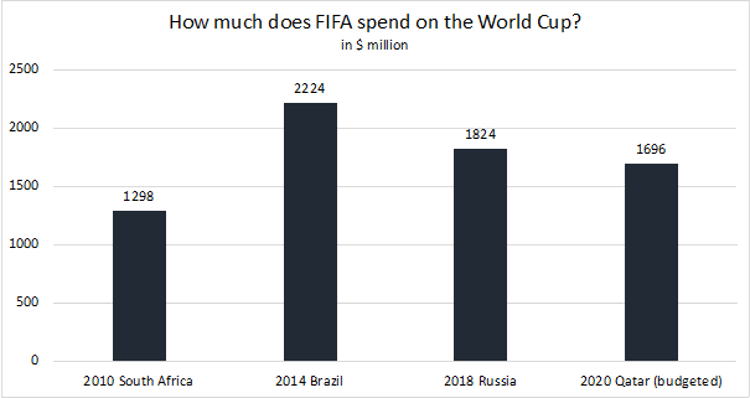

As organising body, FIFA spends a significant amount of its total expenditures on the World Cup. During the 2015-2018 cycle, 34 percent of FIFA’s total expenses was spent on the World Cup, while this was even 41 percent during the 2011-2014 cycle.

In FIFA’s 2020 Financial Report, the budgeted cost for the 2022 FIFA World Cup Qatar was set at $1.696 billion. The highest cost item is prize money. With $440 million this makes up 26 percent of total budgeted cost. Operational expenses make up 19 percent and amount to $322 million.

Other major cost items are TV operations and workforce management. The Club Benefits Programme, where FIFA shares part of the World Cup benefits with participating players’ clubs, amounts to $209 million.

FIFA’s budgeted cost 2022 World Cup Qatar

| Category | Cost |

|---|---|

| Prize money | $440 million |

| Operational expenses | $322 million |

| Tv operations | $247 million |

| Club Benefits Programme | $209 million |

| Workforce management | $207 million |

| Team services | $117 million |

| ICT | $49 million |

| Marketing rights delivery | $33 million |

| Other FIFA world cup items | $72 million |

| TOTAL | $1,696 million |

Cost of previous World Cups

FIFA’s budgeted cost for the 2022 edition is lower than what the organisation eventually spent on both the 2014 and 2018 editions, but more than the 2010 edition.

An amount of $1.298 billion was spent by FIFA on the 2010 tournament in South Africa. The 2014 World Cup in Brazil cost $2.224 billion, while expenditures for the 2018 edition in Russia amounted to $1.824 billion.

Payment to cover Local Organising Committee costs

Apart from tournament costs and contributions to member associations (prize money and preparation compensation) and clubs (Club Benefits Programme), FIFA also funded the Local Organising Committee (LOC) in previous editions.

Apart from tournament costs and contributions to member associations (prize money and preparation compensation) and clubs (Club Benefits Programme), FIFA also funded the Local Organising Committee (LOC) in previous editions.

For the 2018 World Cup in Russia, FIFA contributed $383 million to LOC operations. The budgeted cost was $627 million (from 2011-2018), but “major savings were achieved in the areas of transport (air and ground), IT & telecoms and security as well as in the functional budgets” resulting in $244 million in savings. This contributed to FIFA coming in $124 million under budgeted cost for the whole 2018 event.

The 2010 South African Organising Committee made a slight profit of $10 million (based on at that time provisional figures). $226 million in direct contributions from FIFA and $300 million coming from ticket sales passed on by FIFA made up the revenue.

On the other hand, operational expenses amounted to $516 million. Part of the costs came from stadium operation ($260 million), personnel costs ($58 million), transport ($34 million) and information technology ($26 million).

The 2006 German Organising Committee made a profit of €156 million. The LOC could keep €111 million as part of a prior agreement with FIFA about any surplus recorded. The total cost had amounted to €400 million and primarily came from event, advertising, and travel cost (€211 million) and third-party services (€102 million).

Joint venture Qatar and FIFA

For the 2022 World Cup Qatar there is no longer an independent LOC. In February 2019, FIFA announced the creation of the joint venture FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 LLC.

The governing body holds 51 percent of the shares, while the Qatar 2022 LOC holds the other 49 percent. The company will plan and deliver operations and services for the tournament. By working together, they hope to avoid inefficiencies and thus eventually keep cost lower.

Benefits overstated and costs understated

However, where FIFA and even the LOCs can make a profit from world’s biggest single-sport event, host countries often do not make a return on their investment. The benefits are numerous, but usually difficult to measure and overstated during the bid procedure and to the community leading up to the event. While costs tend to be understated.

However, where FIFA and even the LOCs can make a profit from world’s biggest single-sport event, host countries often do not make a return on their investment. The benefits are numerous, but usually difficult to measure and overstated during the bid procedure and to the community leading up to the event. While costs tend to be understated.

The benefits mentioned for holding a World Cup are both monetary and non-monetary. Apart from the boost it can give to a country’s football ecosystem in the short- and long-term, staging a major event and projecting a positive image to the world could well lead to more tourism. Furthermore, investments in infrastructure will benefit local citizens and extra (temporary) jobs are created. South Africa’s LOC, for example, projected that the tournament would create 159,000 extra jobs.

Yet, there is little to no long-term boost to the economy. Before the 2006 World Cup in Germany, few believed the event would have more than a minimum effect on the country’s gross domestic product. After the successful hosting of the event, Axel Weber, head of Germany’s central bank, said that “the current feel-good sentiment is a short-term phenomenon” and that it does not have a lasting positive effect on the economy. It did have an enormous positive impact on the country’s image, according to Michael Glos, Economy Minister at the time.

A study concluded that the tournament earned Germany’s tourism industry €300 million ($399 million) in extra revenue, increased retail sales by €2 billion and resulted in 50,000 new jobs. In addition, the treasury received €40 million from ticket sales and €44 million in taxes over the LOC’s profit.

Total cost incurred by host nations

It is extremely difficult to pinpoint what countries have spent on hosting the World Cup. Which investments are included and how honest are governments and contracted parties about the amount spent when it surpasses budgets and there is backlash from the community? It is therefore only logical that reported values differ and must be taken as rough estimates.

The cost of infrastructure around the 2006 World Cup is said to have reached €3.7 billion for Germany. That is a lot less than what Japan and South Korea supposedly spent on construction and infrastructure for the 2002 edition, with amounts of $6.5 billion – $4.5 billion in Japan and $2 billion in South Korea – and $7 billion mentioned.

South Africa projected public investment to reach over $944 million. However, official figures set total cost at $4.3 billion. The planned expenses for stadium construction (six) and renovation (four) practically doubled to $1.7 billion. Apart from infrastructure, security represented a major expense for South Africa. The authorities spent more than $197 million to get security up to scratch in a bid to persuade visitors worried about the country’s high crime rate.

Brazil spent an estimated $15 billion on the 2014 World Cup, slightly more than Russia. Projected cost for the 2018 tournament was set at $11.6 billion, but figures ultimately reached over $14 billion. With transport infrastructure ($6.11 billion), stadium construction ($3.45 billion) and accommodation ($680 million) being the main contributors.

What the cost will be for Qatar remains to be seen and like previous editions the exact cost will likely never be known. The bid documents reported a stadium construction and renovation budget of around $3 billion (this still included three stadium renovations and nine new stadiums). However, apart from stadium infrastructure, the country has invested heavily in other infrastructure, including a metro network, roads, hospitals, and a new airport. All part of the country’s broader long-term plans and these investments will cost Qatar more than $200 billion.

Estimated cost for World Cup host countries

| World cup | Estimated cost (excl. inflation adjustments) |

| 2002 South Korea/Japan | $6.5 – $7 billion |

| 2006 Germany | €3.7 billion |

| 2010 South Africa | $4.3 billion |

| 2014 Brazil | $15 billion |

| 2018 Russia | $14.2 billion |

Qatar 2022 went from 12 to eight stadiums

That a host country must invest a lot of money to comply with regulations is evident. The construction and renovation of venues is one of the largest expenses, but the amount needed is heavily dependent on the current state of stadiums.

France (1998), for example, had to spend little compared to other host nations as a lot of the stadium infrastructure was already present. The country had numerous football stadiums across the country available and mostly used renovated venues. Only Stade de France, currently the national stadium of the country, was built for the event. With France spending €364 million on the 80,000-capacity venue.

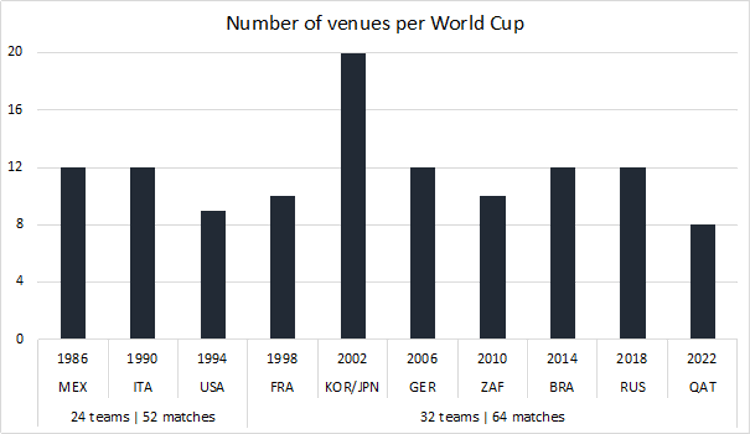

In their bid, Qatar said they would build 12 stadiums, FIFA’s preferred number of venues. However, in the end the organisation has opted for only eight stadiums. The lowest number during the past ten editions. FIFA accepted the lower number of venues, and it does make sense for a country with less than three million inhabitants and where the venues are within a radius of 60 kilometres of one another. Moreover, nine out of the 12 stadiums had to be built from scratch, increasing cost even more.

Apart from reducing the number of stadiums, Qatar will also have temporary stadiums and seating. Stadium 974 will even be the first temporary World Cup stadium. Made from 974 recycled shipping containers, it will be deconstructed after the event. The modular sections will then be used to construct 22 stadiums in developing countries.

Overall, the stadiums will have relatively limited capacity with six out of eight venues having a capacity under 46,000, but above FIFA’s preferred minimum of 40,000. This will lower income from ticket and corporate hospitality sales, but all these measures will hopefully prevent (too many) ‘white elephant’ stadiums.

‘White elephant’ stadiums not the desired legacy

‘White elephant’ stadiums, “costly stadium projects (both in terms of construction and maintenance) considered disproportionate to their frequency of use and legacy”, is something FIFA wishes to avoid and considers during the bidding process. Research done for FIFA showed that optimal stadium capacity depends on various factors, but a city’s population is of great importance.

‘White elephant’ stadiums, “costly stadium projects (both in terms of construction and maintenance) considered disproportionate to their frequency of use and legacy”, is something FIFA wishes to avoid and considers during the bidding process. Research done for FIFA showed that optimal stadium capacity depends on various factors, but a city’s population is of great importance.

Previous editions have shown the need to take the stadiums’ legacy into account. Brazil has been left with several white elephants from the 12 stadiums that they built for the 2014 World Cup. Costs exceeded budgets and stadiums in cities like Manaus and Cuiabá were hardly used with no major local football teams or culture.

2002 co-hosts South Korea and Japan had a record 20 venues, with most of them built for the tournament. It was one of the main causes that led to the high expenditures for the two Asian countries.

Money-draining venues after the World Cup

Most of these stadiums sit idle and are money-draining venues after the World Cup. The 63,700-seat stadium in Saitama, Japan, for example, cost around $667 million to build. In the wake of the tournament, it only hosted a local professional football club with an average attendance one-third of the stadium’s capacity. At the time, it was estimated that the stadium’s maintenance costs would amount to $6 million annually, while local games would only generate 40 percent of that in income.

A similar image emerged after the 2010 World Cup in South Africa. Poor national league attendance led to near-empty stadiums. At the same time, the World Cup-stadiums have high annual maintenance cost. The 54,000-seat Cape Town Stadium is said to cost £2.4 million yearly to maintain, but there is little revenue to offset it. Apart from some high-profile international concerts, these stadiums sit idle most of the year. Almost as a last resort, some teams are being paid to play their home matches at the stadiums.

Even 1998 host France has incurred stadium costs in the years following the event. In 2013, the France government was able to suspend a yearly €16 million payment to the consortium managing Stade de France. Since its opening, the government had spent €114 million on the venue, almost one-third of its original reported cost.

Co-Hosting More Popular

The high costs and doom scenarios from the past, do not reduce countries’ desire to host the World Cup. However, a shift seems to take place, where multiple countries join forces to submit a combined bid. The 2026 World Cup, for example, will be hosted by Canada, Mexico, and the USA. While multiple joined bids are expected to be submitted for the 2030 edition.

The high costs and doom scenarios from the past, do not reduce countries’ desire to host the World Cup. However, a shift seems to take place, where multiple countries join forces to submit a combined bid. The 2026 World Cup, for example, will be hosted by Canada, Mexico, and the USA. While multiple joined bids are expected to be submitted for the 2030 edition.

Spain and Portugal will join forces, just as Greece, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, members of three different confederations. While a quartet of South American countries – Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, and Paraguay – will also submit a bid.

In the past only South Korea and Japan co-hosted the World Cup. Their decision to have 20 venues, 10 each, led to high costs. The new trend of multiple nations joining forces is likely caused by the desire to lower cost as a host nation.

Most nations have one or a few stadiums that can comply with FIFA’s strict stadium regulations and if not, require only limited renovations. Co-hosting will therefore reduce the need for (many) new stadiums and the amount of ‘white elephant’ stadiums. Something that can be observed from UEFA Euro 2020, that was held across the European continent in 11 existing stadiums.

Confirmed to bid for the 2030 World Cup

| Countries | Confederation(s) |

|---|---|

| Morocco | CAF |

| Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Paraguay | CONMEBOL |

| Spain and Portugal | UEFA |

| Greece, Saudi Arabia, Egypt | UEFA, CAF, AFC |

Expansion to 48 teams

A desire to lower construction cost is especially useful since the World Cup is expanding to 48 teams from 2026 onwards. Instead of 64 matches, 80 matches will be played. With the amount of teams increasing by 50 percent and the number of matches by 25 percent, it will surely increase total cost for the host nation(s).

A desire to lower construction cost is especially useful since the World Cup is expanding to 48 teams from 2026 onwards. Instead of 64 matches, 80 matches will be played. With the amount of teams increasing by 50 percent and the number of matches by 25 percent, it will surely increase total cost for the host nation(s).

On the other hand, FIFA will earn more from the format change. So much so, that FIFA tried to expand the 2022 edition to 48 teams in 2019. A feasibility study found that if one of Qatar’s neighbours would have become an additional host, with two to four venues, it could have generated an additional $400 million in revenue. This would include among others $121.8 million from broadcasters, $158.4 million from sponsors and $89.9 million more from ticket sales.

It did not happen, and the new format will now be introduced in 2026, but it is clear why FIFA wanted it. The question is how host nations will benefit. The higher number of matches, and thus fans, will have a positive effect on tourism numbers. But with more nations the overall match quality could well decrease, leading to fans getting pickier about the matches they will attend.

Despite all of it, the appeal of the World Cup is so large that nations keep bidding for the tournament. Even if costs in the lead up to, during and even after the event, are generally not offset by the benefits hosting may generate. With the World Cup expanding to 48 teams and more nations choosing combined bids and thus sharing costs, hosting the event may become more profitable.