Curbing Football Club Spending With UEFA’s Financial Stability Regulations

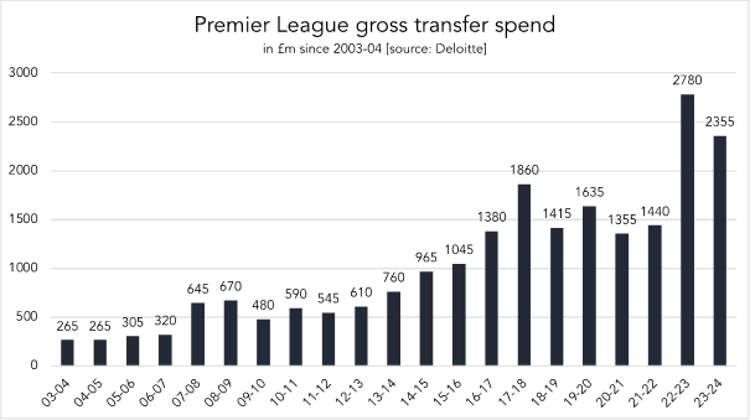

Premier League clubs spent £2.36 billion on transfer sums during the 2023 summer transfer window. An increase of almost 23 percent compared to the summer prior. While the clubs spent just 11 percent (£265 million) of that during the 2003-04 season. Apart from La Liga, gross summer transfer spending increased across all big five leagues in 2023.

With total spend increasing year-on-year by almost 26 percent, to €5.68 billion, according to Deloitte. Add to that, the big and bold stance of the Saudi Pro League in the transfer market, and it seems unlikely spending will slow down any time soon.

Premier League club Chelsea alone, has spent around £1 billion on player acquisitions since Todd Boehly took over in May 2022. With the summer signing of Ecuadorian midfielder Moisés Caicedo for around £115 million, the London club holds the British transfer record. Amongst Manchester City’s signings, there were three players that cost them over £50 million in the 2023 summer transfer window.

However, the Premier League still investigates last season’s treble winners for over 100 financial rules breaches. In La Liga, clubs walk a tightrope to establish a competitive squad while adhering to the league’s financial rules. With clubs like Barcelona asking players to restructure their contracts to register new players.

These situations lead to raised eyebrows and questions amongst fans. With UEFA’s and leagues’ financial regulations, how can clubs spend this much? What kind of financial regulations do governing bodies have in place to curb spending?

And how are clubs, who have done foul of the rules sanctioned?

What financial regulation does UEFA have and why?

In the 2003-04 season, UEFA introduced the UEFA club licensing system to fulfil clubs’ desire for regulation to tackle mismanagement and raise standards in European football governance. To further improve the overall financial health of European club football, UEFA expanded their regulation with a financial sustainability system in 2009. It took effect in the 2011-12 season through Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations.

In the 2003-04 season, UEFA introduced the UEFA club licensing system to fulfil clubs’ desire for regulation to tackle mismanagement and raise standards in European football governance. To further improve the overall financial health of European club football, UEFA expanded their regulation with a financial sustainability system in 2009. It took effect in the 2011-12 season through Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations.

Since the introduction of FFP, clubs that qualify for European competitions must prove they have no overdue payables throughout the season. This means clubs are assessed on whether they pay other clubs, their staff (including players) and taxes on time.

Three years later (2013), UEFA added the break-even requirement that focusses on a balance between spending and revenue and on preventing the accumulation of debt.

Major changes to UEFA’s financial regulations since 2003

2003

Introduction of UEFA club licensing system

2009

Introduction of a financial sustainability system

2010

Approvement of Financial Fair Play regulation

2011

First assessment of Financial Fair Play regulation. Main element – no overdue payables

2013

Expansion of Financial Fair Play regulation. Added – break-even requirement to balance spending and revenue

May 2014

First assessment of the break-even requirement and sanctions

June 2022

Introduction of UEFA Club Licensing and Financial Sustainability Regulations. 3 key pillars – solvency, stability, and cost control

June 2023

Update to the UEFA Club Licensing and Financial Sustainability Regulations

Positive effect of UEFA’s financial sustainability system

So far, the financial sustainability system implemented by UEFA has had a positive effect on the financial status of European club football. Overdue payables are almost non-existent. In addition, clubs’ financial performance has improved.

So far, the financial sustainability system implemented by UEFA has had a positive effect on the financial status of European club football. Overdue payables are almost non-existent. In addition, clubs’ financial performance has improved.

In 2009, net losses across clubs from Europe’s biggest leagues stood at €1.6 billion. By 2018, this had turned into a profit of €140 million. Since then, the COVID-19 pandemic caused reported losses of €7 billion across the board, altering European football’s financial situation.

Financial sustainability focuses on three key elements

The pandemic has shown that European football is still vulnerable to unforeseen events and requires regulations to deal with this and other market changes. In 2023, UEFA therefore implemented further updates to its financial sustainability regulations, now called the UEFA Club Licensing and Financial Sustainability Regulations.

The pandemic has shown that European football is still vulnerable to unforeseen events and requires regulations to deal with this and other market changes. In 2023, UEFA therefore implemented further updates to its financial sustainability regulations, now called the UEFA Club Licensing and Financial Sustainability Regulations.

The licensing part ensures clubs meet the minimum criteria with respect to sporting, football social responsibility, infrastructure, personnel, and administrative, legal, and financial criteria. While the financial sustainability of clubs is monitored by the UEFA Club Financial Control Body. The framework consists of three key pillars: solvency, stability, and cost control.

Three key pillars of UEFA’s Financial Sustainability Regulations

| What | How |

|---|---|

| Solvency | No overdue payables. |

| Stability | Control costs and spend in relation to revenue generated. |

| Cost control | Spending on player and coach wages, transfers, and agent fees limited to 70 percent of club revenue. |

Solvency requirements: no outstanding debt

The first pillar consists of solvency requirements. Solvency is the ability to pay one’s debt. On 15 July, 15 October, and 15 January each season, clubs can have no overdue payables, e.g., no bills that must still be paid. This ensures the protection of creditors. So, those parties that receive money for services rendered or goods sold.

This could be other football clubs who are entitled to payments in the form of transfer sums, players receiving their wages and/or bonuses, authorities receiving taxes over revenue or governing bodies, like UEFA themselves, receiving financial contributions from sanctions.

UEFA implemented this as one of the first rules in its financial sustainability programme back in the day and with success, as overdue payables are almost non-existent for those playing European club football.

Stability through the football earnings rule

The second pillar, stability, aims for clubs to control their costs and to spend in relation to the revenue they generate. It is implemented through the football earnings rule that requires clubs to have an aggregate football earnings deficit within the acceptable deviation over a monitoring period of three years.

It replaced the former break-even requirement.

What income and costs are considered relevant?

UEFA defines football earnings as the difference between relevant income and expenses for a reporting period of one financial year. Relevant income consists of earnings that come from such sources as gate receipts, sponsorship plus advertising, broadcasting rights, commercial activities, UEFA solidarity and prize money and other operating income. Another form of relevant earnings is generated by the profit of selling players.

UEFA defines football earnings as the difference between relevant income and expenses for a reporting period of one financial year. Relevant income consists of earnings that come from such sources as gate receipts, sponsorship plus advertising, broadcasting rights, commercial activities, UEFA solidarity and prize money and other operating income. Another form of relevant earnings is generated by the profit of selling players.

How this is calculated depends on a club’s method of accounting for player registrations in its financial statements. For a club that uses the capitalisation and amortisation method of accounting for player registrations, it is the difference between the transfer sum and the book value of a player (dependent on factors such as the transfer sum when a player was acquired, amortisation, and remaining contract length) at the time of the sale. For those using the income and expense method, it is the income minus relevant costs to transfer the player registration to another club and should equate the monetary income of such a sale.

Relevant costs cover expenses such as costs of sales/materials, employee benefit expenses for players and other personnel, and other operating expenses. But also, the amortisation of player registrations and/or cost of a player’s registration. And the loss in case a player is sold for an amount below its book value. Similar costs can be incurred for non-playing personnel, such as the technical staff and are also included in relevant costs.

Relevant elements for calculating football earnings

| Relevant earnings | Relevant costs |

|---|---|

| Gate receipts | Costs of sales/materials |

| Sponsorship and advertising revenue | Employee benefit expenses for players |

| Broadcasting rights revenue | Employee benefit expenses for other employees |

| Revenue from commercial activities | Other operating expenses |

| UEFA solidarity revenue and prize money | Amortisation/impairment of player registrations and/or costs of a player’s registration |

| Other operating income | Loss on disposal of player registrations |

| Profit on disposal of player registrations and/or income on disposal of player registrations | Amortisation/impairment of release costs for other personnel or release costs for other personnel |

| Excess proceeds on disposal of tangible assets | Other non-operating expense |

| Other non-operating income | Finance costs and dividends |

| Finance income | Expense transaction(s) below fair value |

| Foreign exchange result | Non-monetary debits/charges |

| Non-monetary credits/income | Expenditure directly attributable to non-football operations not related to the club |

| Income from transaction(s) above fair value | Financial contribution set out in a settlement agreement with the CFCB and/or a financial contribution imposed by the CFCB in respect of the stability and/or cost control requirements |

| Income from non-football operations not related to the club | |

| Income in respect of a reduction of liabilities arising from procedures providing protection from creditors |

Excluded are earnings or expenses such as the sale of tangible assets (e.g., stadium), intangible assets other than player registrations or other personnel’s release costs and tax related amounts.

Aggregate football earnings monitored over three years

Where football earnings are calculated over a reporting period of one financial year, UEFA also applies a monitoring period of three consecutive reporting periods. Aggregate football earnings are the sum of football earnings across that monitoring period.

Where football earnings are calculated over a reporting period of one financial year, UEFA also applies a monitoring period of three consecutive reporting periods. Aggregate football earnings are the sum of football earnings across that monitoring period.

A club adheres to the football earnings rule when its aggregate football earnings are positive or negative within the acceptable deviation of €5 million. The deficit is allowed to be a maximum of €60 million if it is entirely covered by either, contributions in the latest reporting period or through equity at the end of it. The deviation has increased from €30 million in the past seasons after it was €45 million during the 2013-14 and 2014-15 seasons. UEFA hereby puts emphasis on equity contributions rather than debts.

Aggregate football earnings for a monitoring period can be adjusted, favourably, with relevant investments for the long-term benefit of football. These are, for example, investments in youth development, community development and women’s football. Also included are costs directly related to construct or substantially renovate tangible assets, like a stadium or training centre.

In addition, UEFA gives more leniency, in the form of a higher acceptable deviation of the football earnings rule (of up to €10 million for each reporting period), to clubs with a healthy financial status. With financial health being measured through key indicators such as positive equity, a quick ratio (total current assets less inventories divided by total current liabilities) equal to or above one and a sustainable debt ratio.

The importance of fair value

One issue highlighted by UEFA in its regulation is that of fair value of services rendered and goods sold and bought. Fair value is the amount for which an asset or service could be traded between willing parties. This could mean the fair value for which a player is bought and sold, but also the value of sponsorship deals.

One issue highlighted by UEFA in its regulation is that of fair value of services rendered and goods sold and bought. Fair value is the amount for which an asset or service could be traded between willing parties. This could mean the fair value for which a player is bought and sold, but also the value of sponsorship deals.

When clubs and sponsorship partners have owners who are in one way or another related, they could potentially inflate the value of sponsorship agreements. This would mean a higher listed relevant income, making it ‘legal’ to spend more on players acquisitions and wages while abiding by UEFA’s football earnings and squad cost regulations.

UEFA enlists the help of independent third-party assessors who perform an assessment conform to standard market practices and ascribe a fair value to transfers or sponsorship deals. This makes the process less arbitrary.

Manchester City’s sponsorship deals

Monerals, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

One club under scrutiny in recent years for possible financial rules breaches is Manchester City. The club is now under investigation by the Premier League, but allegations already surfaced in 2019. UEFA’s Club Financial Control Body (CFCB) alleged City breached FFP regulations by misstating income sources.

Furthermore, the club allegedly did not give a true and fair representation of income streams. In other words, they may have overvalued sponsorship agreements with related parties. It led to a two-year suspension from the Champions League and a €30 million fine by UEFA in February of 2020. However, the club successfully appealed the ban at the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS). Who also reduced the fine to €10 million, stating statute of limitations as reason for overturning UEFA’s sanctions.

Overvalued swap deals

![]() In addition to sponsorship deals, clubs sometimes also overstate transfer sums above fair value. This could especially happen in the case of swap deals between clubs. In the Italian plusvalenza (Italian for capital gain) case, multiple clubs allegedly inflated the value of transfer sums for financial gain.

In addition to sponsorship deals, clubs sometimes also overstate transfer sums above fair value. This could especially happen in the case of swap deals between clubs. In the Italian plusvalenza (Italian for capital gain) case, multiple clubs allegedly inflated the value of transfer sums for financial gain.

Clubs obtain an advantage through the concept of amortisation. An accounting process of gradually writing off the initial cost of an asset. In football, clubs generally amortise the transfer fees (initial cost) of players (assets). At first sight, one may think when there is a swap deal that income and expenses off-set each other (in case of equal transfer sums). However, player sales are immediately booked as income. While the amount spent on buying players can be amortised over a player’s contract length.

A swap deal (especially one above fair value) gives a club financial gain and time by having more income now, while the costs are spread over future years.

Juventus’ role in the plusvalenza scandal

forzaq8 from kuwait, kuwait, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

At the heart of the plusvalenza scandal was Juventus, who the prosecutor said were involved in 42 such suspicious transactions (with reported capital gains of €282 million) between 2018-19 and 2020-21.

The most notable one was the Pjanic-Arthur swap deal. In the summer of 2020, Juventus sold Miralem Pjanic for €60 million to Barca, while his market value was reportedly closer to €45 million. The club bought Arthur Melo for €76 million, while estimations of his market value were around €56 million. It was alleged that the deal was above fair value to the advantage of both clubs, with both rumoured to face financial difficulties.

Juventus were sanctioned for their part in the plusvalenza scandal with point deduction in the Serie A. For breaching UEFA’s regulations, the governing body excluded the Italian side from playing European football (they qualified for the Conference League) in 2023-24 and imposed a €20 million fine (of which €10 million conditional).

Changing rules

It is completely legal for clubs to use amortisation in their favour, if they report assets (i.e., player registrations) at fair value.

It is completely legal for clubs to use amortisation in their favour, if they report assets (i.e., player registrations) at fair value.

Chelsea’s new owners found a ‘loophole’ to take advantage of this in the short term. Since UEFA allowed amortisation to take place over the length of a players’ contract, the London club acquired multiple players on long-term contracts in the 2022-2023 January transfer window. Mykhailo Mudryk, for example, signed a record eight-and-half year contract.

This meant that Chelsea can spread out the reported £88.5 million transfer fee over that period (around £10.4 million per year). Despite the same overall impact, the financial impact per year is lower. The club could therefore more easily comply with financial regulations in the short term, despite the high overall cost. Of course, future earnings should be enough to cover the yearly amortisation, but in the short-term clubs can theoretically invest more.

Five recent incoming Chelsea transfers on long-term contracts

| Player | From | Transfer sum | Contract length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzo Fernandez | Benfica | £106.8 million | 8.5 years |

| Mykhailo Mudryk | Shakhtar Donetsk | £88.5 million | 8.5 years |

| Benoit Badiashile | Monaco | £35 million | 7.5 years |

| Noni Madueke | PSV | £29 million | 7.5 years |

| Malo Gusto | Lyon | £26.3 million | 7.5 years |

UEFA rule change: amortisation over maximum five years

However, it can be a risky move if future earnings cannot cover the yearly amortisation sums. To combat this, UEFA set a maximum of five years to amortise transfer fees in February 2023.

However, it can be a risky move if future earnings cannot cover the yearly amortisation sums. To combat this, UEFA set a maximum of five years to amortise transfer fees in February 2023.

So, in the past if clubs bought a player for £60 million and gave him a six-year contract, the club would write down £10 million each year (=60/6).

Now clubs can only do so over max five years, irrespective of contract length. In this case it means clubs must write down £12 million (=60/5) each year.

There is more to it than just transfer sums

The financial situation of clubs around transfers is thus not as simple as the image the public receives of incomings and outgoings from the numerous lists of net transfer spend.

The financial situation of clubs around transfers is thus not as simple as the image the public receives of incomings and outgoings from the numerous lists of net transfer spend.

Reported transfer sums only tell part of the story. In addition to transfer sums, there are signing-on bonuses, wages, and agent fees.

For example, club A can acquire a player for a higher transfer sum than club B acquired their player for. However, club B may pay far more yearly wages. Over the length of the contract, this could mean club A spends less.

Controlling cost with the new squad cost rule

Football’s greatest challenge remains cost control. Club stakeholders (owners, players, fans) want on-field success as in any other sport. In this sense it deviates from other businesses, who often aim for profit maximisation. The preference for sporting success over financial success, means that football clubs get tempted to invest heavily in assets, in the form of talented players, while foregoing the importance of balancing budgets.

Football’s greatest challenge remains cost control. Club stakeholders (owners, players, fans) want on-field success as in any other sport. In this sense it deviates from other businesses, who often aim for profit maximisation. The preference for sporting success over financial success, means that football clubs get tempted to invest heavily in assets, in the form of talented players, while foregoing the importance of balancing budgets.

Since the introduction of financial sustainability regulation, UEFA has tried to limit overspending with first the breaking-even requirement and now the football earnings rule. However, transfer sums and wages have not truly slowed down because of these rules. Since 2023, UEFA has implemented the extra measure of cost control through squad cost regulations that limits spending on player and coach wages, transfers, and agent fees to 70 percent of club revenue.

UEFA gradually implements the rule with a ratio of squad costs to club revenue set at 90 percent in 2023-24, 80 percent in 2024-25 and the final 70 percent from the 2025-26 season onwards.

Gradual implementation of squad cost rule

| Season | Limit of squad costs to club revenue |

|---|---|

| 2022-23 | No limit |

| 2023-24 | 90 percent |

| 2024-25 | 80 percent |

| 2025-26 | 70 percent |

Rise in wages on par with revenue increase

One can say that the new rule is a form of salary cap. Something the European football market has debated about for a long time and is already present in most American leagues.

The inability of the market, the clubs, and the owners, to spend sensibly and sustainably seems to require further intervention. Because apart from rising transfer spending, wage costs have risen significantly as well.

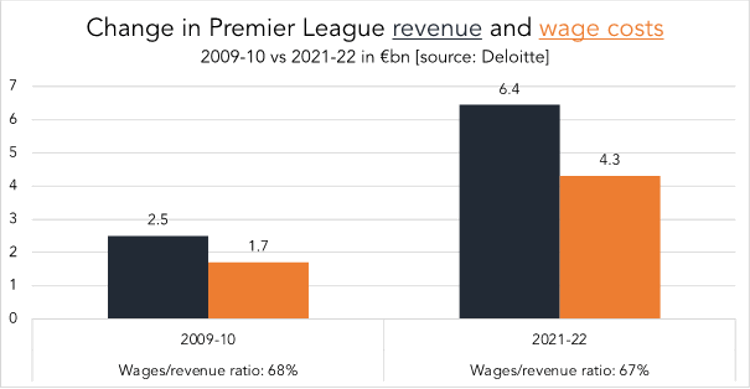

In 2009-10, just before the introduction of FFP, the wages of the big five leagues increased by eight percent to €5.5 billion. In Italy and France wages grew more than the absolute growth of revenue, while England and Germany were on par. The Premier League and Bundesliga were also the only big five leagues to achieve operating profits.

In the Premier league the wages to revenue ratio, as defined by Deloitte, increased to 68 percent that season, the highest it had been at the time. In the Championship the wages to revenue ratio was even at 88 percent, two percent points lower than the season prior, but still extremely high. With even a third of the Championship clubs paying more wages than they generated in revenue.

Despite revenue rising between 2009-10 and 2021-22 from almost €2.5 billion to €6.442 billion, the Premier League’s wages to revenue ratio did not significantly change. With the average wages to revenue ratio amounting to 67 percent in 2021-22 (although it was around 60 percent in the years prior to COVID-19).

Wage costs rose just as fast. Wages went from £1.4 billion (€1.7 billion) in 2009-10 to £3.6 billion (€4.3 billion) in 2021-22. During that same period, the wage bill of a club like Manchester City increased by over 90 percent from £133 million to £354 million.

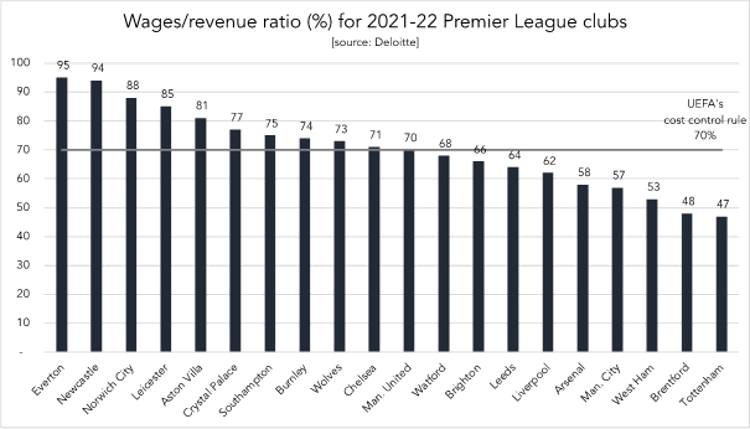

Differences in wages to revenue ratios

There are big differences in wages to revenue ratios between clubs though. Tottenham had the lowest wages to revenue ratio with 47 percent in 2021-22. While Everton and Newcastle United found themselves, with ratios of respectively 95 and 94 percent, in an unhealthy financial situation. They would also not adhere to the cost control regulations implemented by UEFA this season. By qualifying for the Champions League, Newcastle’s revenue will rise, and the ratio will likely decrease. Everton avoided relegation for a second consecutive season. The club is far from European football qualification, but the ratio implies they are also far from a healthy and sustainable financial situation.

It is the so-called top six that had the highest wage costs in 2021-22. Manchester United spent £408 million on wages, 11 percent more than number two Liverpool (£366 million). However, these clubs also generate the most revenue. On average their 2021-22 wages to revenue ratio was 61 percent. While the average wages to revenue ratio for the other 14 Premier League sides was 74 percent.

Had the new cost control rule been implemented last season, two Premier League clubs would not have met the 90 percent limit (assuming Deloitte’s wages/revenue ratio equals UEFA’s new cost control measure). Just half of the clubs would be at or below the 70 percent limit planned for the 2025-26 season. Showing there is still some work to do for clubs, either by increasing revenue or reducing wage costs.

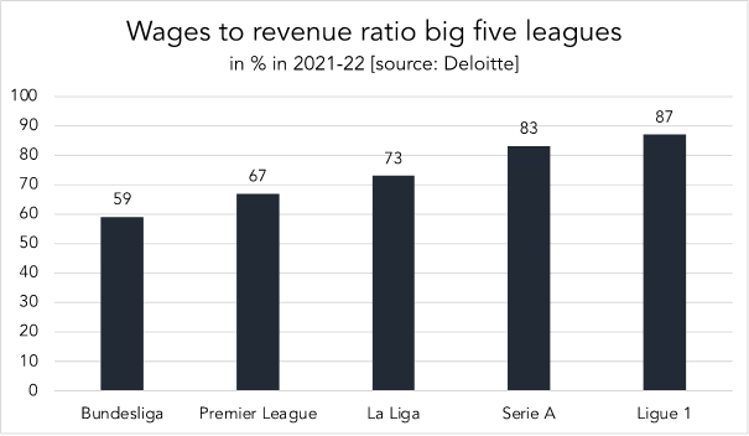

Wages to revenue ratio across big five leagues

The average club wages in the Premier League are also higher than those of its big five league peers. In 2021-22, average club wages were €215 million, up from €195 million the season prior. That is around 80 percent more than the €119 million in average club wages in the 2021-22 La Liga (2020-21: €109 million). In France, average club wages also increased from €79 million to €88 million. While in Germany and Italy it reduced to €103 million and €98 million respectively.

Germany has the best wages to revenue ratio across the big five leagues. This has been the case for quite a while and Bundesliga clubs will likely have the least problems with the new cost control regulations. In 2021-22 the wages to revenue ratio was at 59 percent. Even six percent point lower than the season prior. The Premier League had the second-best ratio with 67 percent. Spain (73 percent), Italy (83 percent) and France (87 percent) all recorded a league wide ratio above the 70 percent. The cost control limit, measuring a similar ratio, will be set at 70 percent from the 2025-26 season onwards and thus below these leagues’ averages.

Critics to UEFA’s financial regulations and enforcement

UEFA’s regulations have had a positive effect on the football market since their introduction. The level of football governance has improved, and overdue payables have almost been wiped out.

UEFA’s regulations have had a positive effect on the football market since their introduction. The level of football governance has improved, and overdue payables have almost been wiped out.

However, since its introduction, it has also faced criticism. One major pain point for many was that it seemed the regulations would ultimately and mostly benefit the established rich clubs. Since those clubs already generate more income, through higher revenue from gate receipts, commercial sources, broadcasting, and prize money, they have more (legal) room to spend. That was the case with the break-even requirement, and with the latest financial restrictions as well.

According to UEFA, these differences in wealth between clubs and countries predated FFP regulations. With the aim of the regulations not to reduce the gap in wealth, but to encourage long-term investments (e.g., in youth and stadium infrastructure) for financial stability and sustainability. In addition, by setting acceptable deviations from the break-even requirement (now the football earnings rule) in absolute terms (million euros) rather than relative (percentage) ones, it is structured to ‘be less restrictive to smaller and medium-sized clubs.’

Lawsuits

Another major concern is the enforcement of regulations. From the public’s point of view, it is often too lenient or not enforced at all. However, there are quite some issues from a legal point of view. The main reason being that UEFA is a European entity and thus must abide by European laws and anti-competition regulation from the European Commission (EC).

Another major concern is the enforcement of regulations. From the public’s point of view, it is often too lenient or not enforced at all. However, there are quite some issues from a legal point of view. The main reason being that UEFA is a European entity and thus must abide by European laws and anti-competition regulation from the European Commission (EC).

The governing body has always tried to work with the EC, the European Parliament, and the Council of Europe (amongst others) to adhere to the laws and regulations and thus make their own financial regulations viable and enforceable. Yet, since its implementation clubs and individuals have entered lawsuits against the governing body.

A famous case is the Striani Complaint. In May 2013, player agent Daniel Striani and his lawyer Jean-Louis Dupont lodged a complaint at the EC against UEFA challenging that the FFP’s break-even rule restricted competition. In July 2015, the ruling of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) gave little merits to the Striani case.

In addition to cases challenging the legality of UEFA’s financial regulations, there have been clubs challenging the sanctions given to them for breaching UEFA’s regulations. Such as Manchester City’s successful appeal of their ban and financial sanctions.

UEFA’s recent sanctions

Most of the sanctions by UEFA from breaking financial regulations are relatively small, unchallenged, and not that visible to the public. The governing body’s goal is to improve clubs’ financial health and therefore often enters settlement regimes. Clubs are given a fine consisting of a fixed part and a conditional part. They are only required to pay the latter in case they do not meet future settlement agreement targets. This process ensures a roadmap to a financially healthy and sustainable situation.

During the 2022-23 season, nine clubs were in the UEFA’s so-called settlement regime. One, LOSC Lille, fulfilled the settlement objectives and could exit the settlement regime. Seven more clubs fulfilled their targets and will continue in the process. While Istanbul Başakşehir did not meet its targets and had to pay a €400,000 fine.

Clubs under settlement regime during the 2022-23 season

| Settlement target | Club |

|---|---|

| Fulfilled and allowed to exit the settlement regime | LOSC Lille (FRA) |

| Fulfilled and continue in settlement regime | AC Milan (ITA), AS Monaco (FRA), AS Roma (ITA), Beşiktas (TUR), Inter (ITA), Marseille (FRA), PSG (FRA) |

| Did not meet targets and was imposed a sanction | Istanbul Başakşehir (TUR) – fine €400,000 |

Barca and United imposed fines by UEFA

During the assessment of the break-even requirement (last time under the former FFP regulations), multiple clubs did not comply and were sanctioned. FC Barcelona, for example, received a fine of half a million euros for wrongly reporting profits on disposal of intangible assets (other than player transfers) during 2002. As these are not counted as relevant income by the governing body.

During the assessment of the break-even requirement (last time under the former FFP regulations), multiple clubs did not comply and were sanctioned. FC Barcelona, for example, received a fine of half a million euros for wrongly reporting profits on disposal of intangible assets (other than player transfers) during 2002. As these are not counted as relevant income by the governing body.

While UEFA imposed a €300,000 fine on Manchester United for minor break-even deficits. The governing body also reached settlement agreements with Royal Antwerp and Trabzonspor for not complying with the break-even requirement. Part of the settlement is a €2 million fine of which €300,000 (15 percent) is fixed and €1.7 million (85 percent) is conditional on the clubs meeting their future settlement agreement targets.

Assessment of the 2022-23 break-even requirement

| Offence | Club | Sanction |

|---|---|---|

| Did not comply with the break-even requirement | Royal Antwerp (BEL)

Trabzonspor (TUR) |

€2 million fine 85% conditional |

| Wrongly reporting profit on disposal of intangible assets (other than players transfers) in financial year 2022 | FC Barcelona (ESP) | €500,000 fine |

| Minor break-even deficits | Man. United (ENG)

Konyaspor (TUR) APOEL (CYP) |

€300,000 fine €100,000 fine €100,000 fine |

| Failing to submit complete and accurate break-even information by the required deadline | Riga (LVA)

Ljubljana (SVN) Bratislava (SVK) |

€10,000 fine |

| Note: break-even requirement covering the financial years 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022. Last time based on, now former, FFP. | ||

Another recent sanction for breaching regulations was that of Juventus, including exclusion from this year’s Conference League and a fine. While Chelsea’s new owners reached a settlement (fine of €10 million) with UEFA over the submission of incomplete financial information related to transactions between 2012 and 2019.

Own regulations by leagues

In addition to UEFA’s financial regulations, leagues often have their own (financial) regulations.

In addition to UEFA’s financial regulations, leagues often have their own (financial) regulations.

La Liga, for example, has a salary cap in place since 2013 and this has had a big impact on Spanish clubs’ ability to spend during and after COVID-19. The Spanish salary cap dictates how much clubs can spend on salaries for the first team as well as other teams.

The rule ensures clubs are solvent and is determined based on the difference between a club’s revenue and its structural expenses and expected debt repayments that season. If a team exceeds its salary cap by the end of the season, spending is limited to only 40 percent of income from the sale of players and contract terminations or restructuring. In the past, this was set at 25 percent (also known as the 1:4 rule) and is now rumoured to increase to 60 percent.

The negative effect of COVID-19 on revenue (e.g., no gate receipts) while little to no change in the wage bill caused many La Liga clubs to have issues. The league made some temporary adjustments, but for many staying within the salary cap is still a major challenge. Which is probably reflected in La Liga being the only big five league where gross transfer spending did not increase this summer.

Barcelona’s predicament

Barcelona’s predicament comes from this as well. Camp Nou has Europe’s highest seating stadium capacity with over 90,000. During the 2018-19 season, Barcelona generated around €159.2 million in revenue from matchdays (19 percent of total revenue). This reduced to just €15.9 million, a tenth, during COVID-19 in 2020-21. As La Liga’s salary cap is dependent on revenue, Barcelona’s squad spending limit reduced to €97.9 million in the summer of 2021-22 and further reduced to minus €144.4 after the 2021-22 winter market.

Barcelona’s predicament comes from this as well. Camp Nou has Europe’s highest seating stadium capacity with over 90,000. During the 2018-19 season, Barcelona generated around €159.2 million in revenue from matchdays (19 percent of total revenue). This reduced to just €15.9 million, a tenth, during COVID-19 in 2020-21. As La Liga’s salary cap is dependent on revenue, Barcelona’s squad spending limit reduced to €97.9 million in the summer of 2021-22 and further reduced to minus €144.4 after the 2021-22 winter market.

The salary limit resulted in Barcelona saying goodbye to Lionel Messi, needing to sell players, asking players for restructuring of their contracts, and even making the risky choice of selling future rights to increase current income.

In the past other leagues, including English highest football leagues, have also considered imposing a salary cap to create a healthier and more sustainable football market. For now, such measures have not yet been implemented, but UEFA’s new rules could triple down to national leagues as well. Something that happened when the governing body imposed new regulations in the past.

Need for financial regulation, but not so easy

So since clubs focus more on on-field success than on financial sustainability, UEFA implemented financial sustainability regulations. It has had positive effects, as the financial health across Europe’s leagues has improved (excluding COVID-19 effects). Still, UEFA and national governing bodies are limited by European laws.

So since clubs focus more on on-field success than on financial sustainability, UEFA implemented financial sustainability regulations. It has had positive effects, as the financial health across Europe’s leagues has improved (excluding COVID-19 effects). Still, UEFA and national governing bodies are limited by European laws.

With the introduction of a squad cost rule, effectively a sort of salary cap, and other tweaks to the legislation, the financial situation of the European football market will hopefully improve further.